At the behest of President Donald Trump, the Texas legislature is in the process of setting forth a blatantly partisan gerrymander,, beyond their prior gerrymander, aimed at increasing the number of Republican Congressional seats from 25 of 38 in Texas to 30 of 38. Their goal is to maintain a Republican House majority in the likely event that Democrats gain seats in the 2026 midterm election. This action has already begun to set off a chain of events. California’s governor Gavin Newsom has pushed for a special election to make an exception to California’s fair redistricting and create its own Democratic partisan gerrymander. On the Republican side we are likely to see Ohio, Florida, Missouri and possibly Indiana follow suit. On the Democratic side both Illinois and Maryland–both already gerrymandered–may seek to squeeze out another Democratic seat. If all that plays out, it will still likely be a net gain for Republicans.

Regardless of one’s party affiliation, one should find this outrageous. If political parties are permitted to craft lines designed to keep them in power, it’s not only undemocratic, it’s antithetical to the Constitution. Either Congress or the Supreme Court need to stand up to this abuse.

Back in 1986, with Davis v. Bandemer, the Supreme Court struggled with finding a threshold and criteria to outlaw partisan gerrymanders–but the court’s decision suggested that it was within their jurisdiction. Unfortunately, given the opportunity, the conservative Roberts Court has failed to intervene, suggesting that blatant partisan gerrymanders are outside the reach of the Judicial branch. With Wisconsin’s blatant Republican partisan state legislative gerrymander, the court punted by saying plaintiffs lacked standing in Gill v. Whitford (2018). In Rucho v Common Cause (2019) the Supreme Court ruled that blatantly partisan Republican gerrymander in North Carolina “presents political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts.” That was decided in a 5-4 conservative-liberal split.

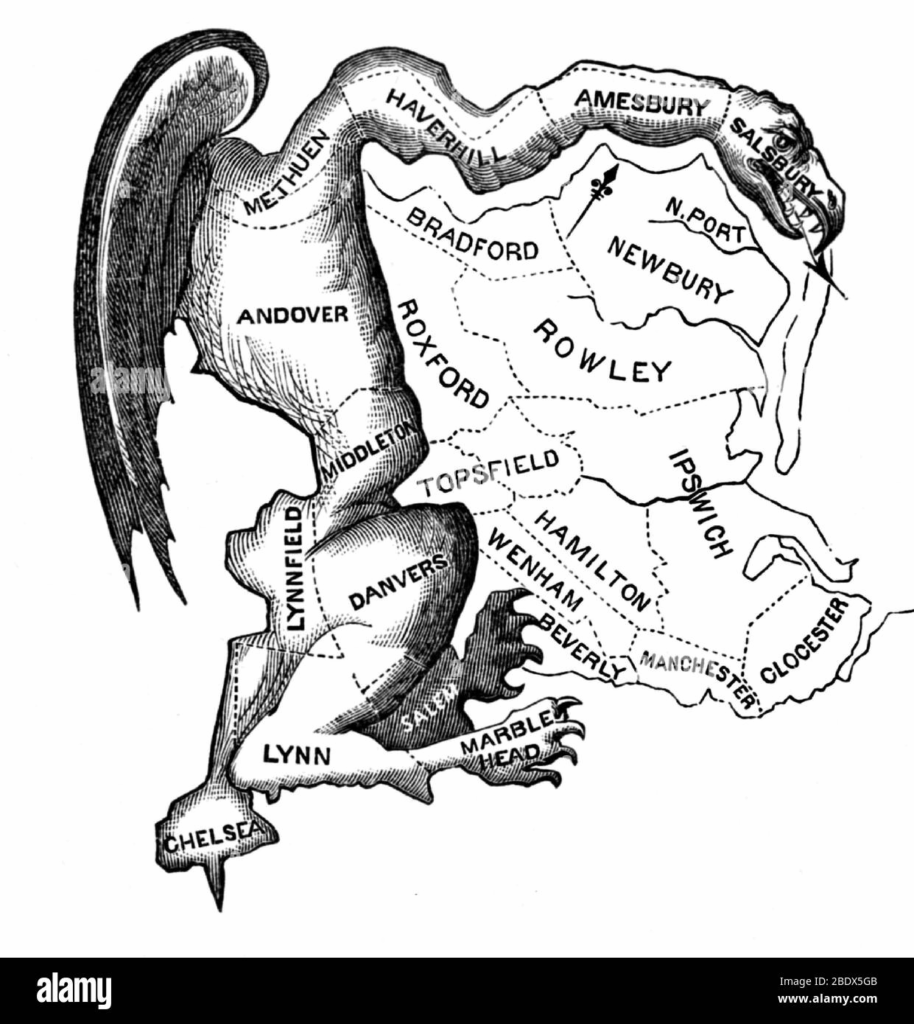

Partisan gerrymanders, unfortunately, have a long history in the United States, going back to one of the Constitutional Convention’s delegates Elbridge Gerry, for whom the salamander-like districts in Massachusetts he helped create as Governor were named a Gerrymander in 1812 to benefit the Democratic-Republican Party.

Racial gerrymanders which should have been outlawed by the 14th amendment’s equal protection clause–were not effectively outlawed until passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. In the Shelby decision in 2013, the Supreme Court struck down the pre-clearance (federal check for racial discrimination) part of the Voting Rights Act, which has led to many Republican states pushing for various measures that make voting harder under so-called “integrity of the vote” claims, but are more generally designed to suppress ethnic and racial groups that tend to support Democrats and in a close election help sway the outcome.

But partisan gerrymanders are far more egregious. Many states, including Arizona, have moved to have independent redistricting, aimed at creating fair districts. These efforts have been far more common in Democratic-leaning states, while Republican states have frequently eschewed that practice. In fact, in Arizona the Republican legislative leadership sued to have Arizona’s redistricting overturned based on the use of “the Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections fo Senators and Representatives , shall be prescribed by each State by the Legislature thereof” in the Constitution–and only by a 5-4 whisker of a decision did the Supreme Court uphold that a citizenry vote represented the equivalent of a legislature in 2015. If not for that, we would be in even worse trouble.

Virtually any observer of the second Trump Administration should be deeply concerned at its often blatantly illegal overreach–which the courts have so far frequently failed to block initially. For instance, Trump’s clams to levy tariffs are highly dubious, yet the courts have not issued an injunction. His tariffs on Brazil, because he dislikes that his friend former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro has been charged with trying to mastermind a coup plot, clearly have nothing to do with any American interest, yet 50% tariffs on Brazilian coffee are now in place.

The mid-decade redistricting circus we are about to witness represents another breaking of the agreed upon norms and guardrails of functional governance, which Harvard political scientists Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt highlight in their 2018 book How Democracies Die.

Partisan gerrymanders bypass voters to secure election outcomes regardless of how people vote.

Congress could intervene under the elections clause of Article 1, which enables Congress to override state rules.

Given Senate rules, this would require a filibuster carve-out. This is something the Senate recently did to make the cost of Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill look less expensive as well as the whole process of budget reconciliation that avoids the filibuster. I had argued on Facebook in 2021 that the same should apply to Voting Rights–including outlawing partisan gerrymanders. Senator Kyrsten Sinema defended the filibuster which blocked it from going forward.

However, the courts can and should intervene on a number of grounds. First, the Founders did not anticipate the role of political parties when the Constitution was developed. The original Constitution under Article II, Section 1, Clause 3 each member of the Electoral College cast two electoral votes. They intended the first to be for President and then the second would be for Vice President–but that was also assuming there would be no political party tickets. That was fine until the 1800 election where the incumbent President John Adams ran with Charles Coatesworth Pinkney for the Federalist Party and the Democratic-Republican ticket was led by Adam’s Vice President Thomas Jefferson who ran with Aaron Burr. One of the electors failed to get the message to not vote for Burr–and Jefferson and Burr tied at 73 electoral votes each–which necessitated a vote in the House of Representatives controlled by the opposing Federalist Party that led to 35 votes without a victor until Alexander Hamilton prevailed upon a few Federalists that led to the Jefferson Presidency and ultimately the 12th Amendment which separated votes for President and Vice President.

So the first point for originalists is that the Constitution disdained political parties.

Second, in the Federalist Papers leading up to the ratification of the Constitution James Madison, particularly in Federalist Paper No. 10 argues about the dangers of factions where a groups of citizens organize in opposition to the common good–and how the Constitution was designed to protect people from such factional interest by controlling its effects. Madison notes, “if a faction consists of less than a majority, relief is supplied by the republican principle, which enables the majority to defeat its sinister views by regular vote.” And if the faction represents the majority? Madison argues, then the majority “must be rendered, by their number and local situation, unable to concert and carry into effect schemes of oppression.”

Clearly, a blatantly partisan gerrymander falls into this Constitutional intention–and is in principle unConstitutional.

Justice Kagan in a concurring opinion in Gill v. Whiford noted that plaintiffs might proceed upon remand that blatantly partisan gerrymanders violate their first amendment right of association. The argument is fairly straightforward in that members of the persecuted political party are being discriminated against in a manner that undercuts their equal protection under the law.

To prove standing plaintiffs must show “invasion of a legally protected interest” (noted above) that is “concrete and particularized”–which means the harm must be real and not abstract–which likely means finding appropriate plaintiffs relative to public policy outcomes that result from a blatant partisan gerrymander.

The best way would be for Congress to intervene–but the whole mid-decade redistricting is designed to prevent that from occurring.

What rule should be used?

Generally, the objective should be that votes should be consistent with the general vote of the populace in statewide elections. I’ll use Connecticut as an illustration. Connecticut has 5 districts–all held by Democrats but tends to vote roughly 60-40 for President or slightly less than that. So generally, districts in Connecticut should give Republicans a reasonable opportunity to pick up at least two Congressional seats. You can see from the Wikipedia page that Republican areas of the state have been carved up a bit especially in Districts 1 and 5. District 5 is the one that has been most carved out to protect a Democrat.

Districts should be contiguous and keep communities whole to the degree practical and favor competitiveness while making sure racial minorities have their voting rights protected.

Since Congress isn’t likely to take this up, send the Supreme Court copies of Federalist Paper No.10 and insist they stop this now.

You can also read and subscribe at my Substack.